Professor Gray was invited to write [a short piece about Massenet’s fairytale opera Cendrillon for the Royal Opera House blog](http://www.roh.org.uk/news/folklore-fairy-tales-and-feminists-cendrillon):

> ### Massenet and the origins of the story

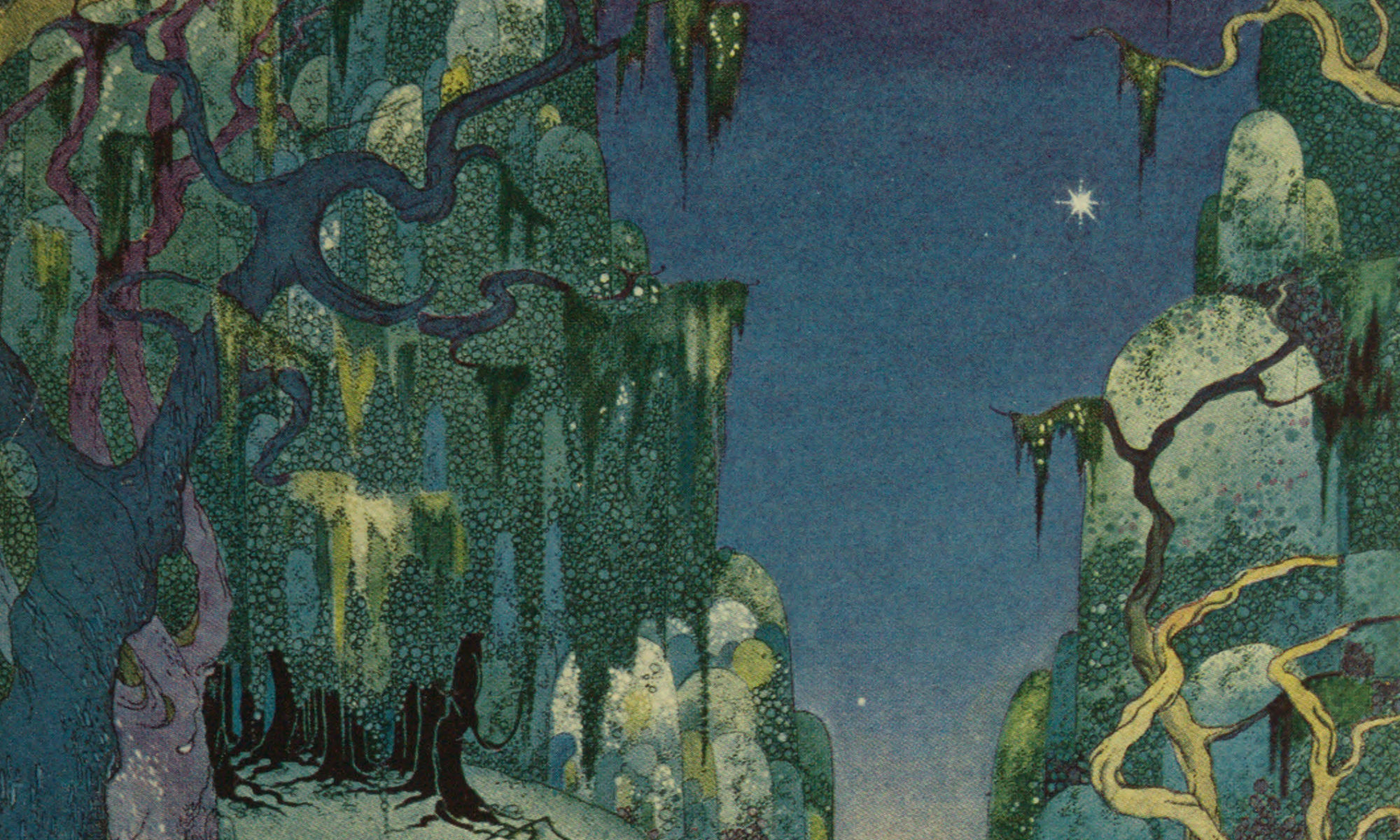

> Cinderella is probably the best known of all fairy tales, with literally thousands of variants all over the world, the most famous being that penned by the 17th-century French author Charles Perrault (albeit based on the pre-existing folk tales). In Massenet’s opera Cendrillon, he and his librettist Henri Cain stick pretty closely to Perrault’s version, though they introduce Cinderella’s flight to the fairy’s magic domain in the country.

> The great variety of the versions of the Cinderella tale all centre round an ill-treated heroine, usually recognized by the prince by means of a shoe. The heroine’s magical helper or donor doesn’t necessarily take the form of a fairy godmother, but can be a magical bird, cow, fish or tree. Grimms’ version of Cinderella (Aschenputtel, sometimes translated Ashypet) has a magic hazel tree instead of Perrault’s fairy godmother.

> It is interesting to note the differences between Perrault’s French Cinderella and the Grimms’ German version, which in several respects has been eclipsed by the former, especially in popular culture. The Grimms’ version—which has no fairy godmother, but a magical tree—is, indeed, much grimmer, with the stepsisters hacking off bits of their foot in order to fit the slipper (the dripping blood gives them away), and having their eyes pecked out at the end of the tale. By contrast, Perrault’s Cinderella, which Massenet follows, has a conciliatory ending, with Cinderella, ‘who was as good as she was beautiful’, taking the repentant sisters to live with her in the prince’s palace and arranging advantageous marriages for them.

> ### What’s the appeal?

> But why do we keep returning to the story of Cinderella and her fabulous transformation? Whole academic institutes exist to study the importance of fairy tales, (including my own Sussex Centre for Folklore, Fairytales and Fantasy at the University of Chichester). Various theories have been proposed to explain why such tales are so deeply embedded in our culture. Such explanations include psychoanalytical theories, expounded by the likes of Freud himself, and other eminent psychologists. The Austrian theorist Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment demonstrated how such tales foster psychological development, while Jung’s archetypes explain the repetition of symbols in myth and folklore.

> Some scholars worry that precisely because fairy tales are so deeply embedded in our psyches and our culture, they have an untold impact on how we experience the world. This is of particular concern to feminist scholars who are critical of the gender stereotypes passed on in fairy tales. They tend to prefer other versions of Cinderella than Perrault’s (and Disney’s) because this Cinderella is too ‘goody-two-shoes’ in comparison with other, more assertive or feisty Cinderella-figures.

> Yet, perhaps most fundamentally, Cinderella has survived as a story for children, passed on from parent to child at bedtime. It still bears repetition, and still works – on a very immediate level – whether as Cendrillon, Cinderella, Aschenputtel or Ashypet. Massenet’s operatic retelling harnesses a very powerful and ancient narrative, and should appeal as much to the seasoned opera goer as a child on their first outing to the opera house.